Which Islam is the true Islam? This is obviously a very volatile question in these turbulent times, and is near impossible to answer. The best conclusion is probably something along the lines of ‘it depends on your interpretation’.

However, even the freedom to explore different interpretations of Islam is highly contested by some (muslims), not recognizing that the absolutist stand in their own view is itself one of many possibilities. This is a hard conundrum, and—while not unique to Islam—is a big sticking point in the Muslim world today.

What I’m trying to do is unpack the different ways in which my early experience as a practicing Muslim defined my relationship to Islam. And how now, I wish to revisit, review, and ‘upgrade’ my 1980’s programming and potentially install a new evolved interpretation for 2015 and beyond :)

This aspiration itself flies in the face of not only orthodox muslim beliefs, but also more mainstream and moderate positions. Indeed, I can feel it pushing my own internal boundaries of what’s ‘allowed’.

The belief that the Quran is the word of God, and cannot be changed, runs deep in muslim hearts and minds. Fundamentalist expressions of such deep convictions continue to lead to much bloodshed today.

While I believe that the Quran was a spiritual revelation that the Prophet Mohammad communicated, what that means to me may be very different to what it means to the next Muslim. How these internal interpretations then go on to shape the values we live by is what’s important.

And these values are shaped at a very early age by our cultural framework. Indeed, the very human example of our parents, our teachers and religious community can create more of an impression on us than the tenets of any religion itself. This couldn’t have been more clearly exemplified by the two different teachers my siblings and I had to teach us how to recite the Quran.

The Two Mullanas

In the early 1980’s, after we had moved to our new home in greater London, my father sat me and my brothers down to teach us how to recite five tenets of Islam, our ‘kalmaai’. This is what we would recite for many years when performing ablutions to purify ourselves before standing in prayer.

It was clear this represented the end of one ‘era’ of our childhood, and we were entering a more ‘grown up’ phase. The first tenet is the proclamation that “There is no God but Allah and the prophet Mohammad is his messenger”. To bear witness to this statement is the foundation of muslim identity.

A few years later, my mother ensured we learnt how to recite the Quran properly, in Arabic. Living out in the suburbs, away from any strong Muslim community, she hired a religious teacher, or ‘Mullana’ to come to our house and provide private tuition.

Innocence Lost

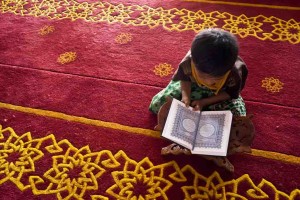

We would lay out a sheet on the living room floor and sit cross legged in a row, each reading out loud the passage we had learnt from our last lesson. Then one by one, we would move to the front of the room to recite our passage to our teacher, or ‘Moli Saab’. Every inflection is specific, and we had a grace period to learn how to enunciate the letters and words correctly.

I loved the sounds, and the melodic quality that I would sometimes manage to hold. But in time, we felt our teacher’s impatience, and his anger, when we would make mistakes. He would often screw up his face in disgust and bark his corrections at each of us as we took turns to recite the passages we had learnt.

I started having a dual association with reciting the Quran. While I willingly embraced the religious context, I also started to associate reciting the Quran with fear and harshness. This latter association only occurred around the tutoring, and was further reinforced when our teacher would sometimes bring other children who he was teaching along with him for our session.

I remember looking on with horror the first time he hit one of them. We were all young, but they were younger still. A boy, who couldn’t have been more than six or seven years old, and an even younger girl who was probably five at the most. They would be reduced to tears, but would dutifully keep reciting through their misery. I felt awful for them, and angry at him. I believe the day our mullana sent the little girl rolling across the floor, we protested to our mother and discontinued our tutoring with him.

Faith Restored

To continue our religious schooling, my parents found another teacher. He couldn’t have been more different. He was younger, he could have been in his early 30’s. He was gentle, sensitive, caring and intelligent. And above all, he wanted us to understand what we were reading.

I loved the fact that he started teaching us basic arabic grammar, sentence construction and tenses. He wanted us to have a foundation for a deeper and first hand understanding of the Quran. I, like many non-Arabic muslims have to read a translation of the Quran to understand what we are reciting. So I loved the more studious approach that accompanied the fulfilling melodic recitation itself.

I still remember him fondly, and was saddened when he could no longer teach us. I believe he fell ill, and sadly passed away well before his time. His gift to us was in demonstrating a tolerant, sensitive and educated relationship to Islam through his own embodied example.

A Matter of Interpretation

So, these two teachers must have interpreted the same religion, the same holy book in very different ways. And no doubt, the cultural and generational context they were each exposed to defined the framework of their interpretation.

What was most important to them? To dogmatically and unquestioningly recite the words correctly—at any cost—or to instill an appreciation for learning and understanding for oneself? I choose the latter, and I hope this practice of inquiry and self-inquiry gains greater momentum over more rigid and intolerant expressions of Islam.

Photo Credits: Firas, Tanti Ruwani, Bengin Ahmad